If pushed for an honest answer, most musicians will admit to experiencing some discomfort, or even perhaps severe pain, whilst playing their instrument, whether it is the clarinet or double bass! Some have had more then their fair share of issues that may even have threatened their future career or ability to continue playing.

Back in 2003 I wrote an article in this magazine headed “The Athletic Musician” (this is still available to read on http://www.theclarinet.co.uk/articles/the-athletic-musician/ ) to provoke some thoughts about how some of these problems arise and what can be done to prevent or reduce the problems. But have we continued to learn how to change our approach to playing our instruments for the better now?

Sadly the major problem can be as a result of an issue beyond our control such as a fall or a car crash. In my case it was the latter which put my career under such severe threat that it still has a bearing on day-to-day life, which includes playing the clarinet.

Returning home from a rehearsal in Leeds on 1 April 1996 (you don’t forget the dates that change your life very easily), I was stationary when my car was at the front of a three-car impact.

Although I was quite concussed from the impact of my head hitting the head restraint very hard, I thought I was uninjured at the time. As I eventually continued my way home it became increasingly apparent that all was not well so I went straight to see Dr. Christopher Mimnagh on the way back to Liverpool. Chris is the Association of Medical Advisors to British Orchestras http://www.bapam.org.uk/amabo.html representative for the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and saxophone/clarinet player himself.

His apocryphal words were “I think you are really going to know about this, as whiplash injuries don’t usually appear immediately after an accident”. But mine did – making their presence felt in my right shoulder, the left side of my neck and in my jaw – the magnitude of the problems grew as the hours passed and would prove to have a huge impact on my clarinet playing.

Five shoulder operations later, and several attempts to correct my jaw problem, resulted in me having to re-evaluate the way I played the clarinet. I had help from many people, but particularly Jo Gibson (the clinical specialist in shoulders at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital). I can honestly say it was her help and persistence over a 15-year period that meant I was not forced to stop playing.

I do not want to make light of the effort required to achieve the improvements, it was, as the title suggests, a great deal of pain without much gain… at the beginning . However, I found myself developing new ways to make my playing easier and pain free. From this I learnt more about what we need to do to play a wind instrument with the greatest economy of effort and least energy input required. I had to rethink and restructure every aspect of my own playing, reducing effort and excess loading wherever possible, I managed to not only get back to playing but improved it in so many ways.

A further positive aspect to come out of my car crash was to work with Chris Mimnagh during my Clarinet Summer Schools, which we have run for 18 years in Liverpool. Chris and I designed a PowerPoint and practical demonstration that revolved around heightened body awareness. As Chris described it, looking at a bunch of clarinettists they will all demonstrate some form of deformity through playing the clarinet. It makes you wonder if the clarinet should carry a government health warning!

As a result of our collaboration Chris recommended me to the British Association for Performing Arts Medicine (www.bapam.org.uk ) to become an advisor/lecturer, helping players to resolve issues with their playing.

Many of us have a concept of what we want from our clarinet playing, or any other instrument. The difficulty lies in knowing which is the best direction we need to follow to achieve our goal.

For most of my playing years my understanding was that as wind players we should develop very strong muscles in the blowing department. In fact, when I first met my physiotherapist Jo Gibson, she took one look at me and asked what I did for a job as she had observed that I had been pulling my spine towards the front of my chest through over developing my abdominal muscles!

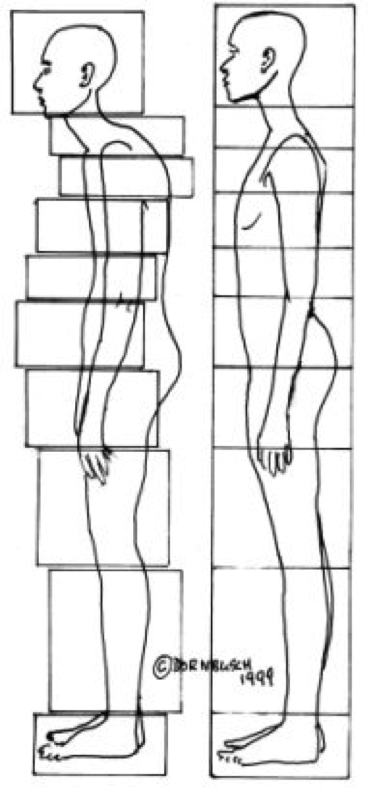

It is often the case that we can observe other people’s bad posture or changes to their physical being but fail to see the problems we may have ourselves. Looking at the diagram above most of us would recognise the less good posture of the guy on the left.

I am now fanatical about the use of mirrors for my personal practice and teaching and have a setup rather like a dance studio, where it is possible to observe my shoulders and back in the mirror in front of me.

Although I am in no way qualified as any sort of medical practitioner, I can make useful observations as a fully qualified “people watcher”. This, in conjunction with my ability to make customisation of instruments, has led to my working with BAPAM as a consultant for players with problems. Sometimes these problems can be caused by something very simple.

I recently worked with someone who has had to take a year out of music college as a result of the pain they were experiencing. I was asked to help with the problem with pain in their shoulder.

Like many people their standing posture inclined to one side. Once they could see the effect on their hip alignment and the muscles of their back it became clear that root cause was in fact their roots! The feet were not supporting the weight of the body due to “rolling out” slightly. This can be solved with custom made orthotic shoe insoles, which can be available free on the NHS through your GP.

After seeing a shoulder consultant the student was relieved to be told categorically that surgery was not required. When referred on to a physiotherapist, confirmation came that the problem lay in not walking in the centre of their feet – and they were subsequently given inserts for their shoes to help. Hopefully a return to Music College is now imminent. The student was very surprised that this issue had gone unnoticed until this point. In no way is this to be regarded as a failure on the part of teachers but it is simply a lack of awareness. This is where BAPAM can help fill this important gap in players and teachers knowledge base.

During last few years I have been invited to most of the UK conservatoires and music colleges to give workshops demonstrating the issues instrumentalists can face and offering some practical advice and exercises that should be compulsory for all musicians; this is usually alongside one of the BAPAM doctors who can field any medical issues that might arise during the workshop or at a later point.

Earlier this year I presented the workshop to RAF bandsmen, and this proved very interesting as they have many issues resulting from gruelling hours on parade and some other less obvious factors. For a simple example the redesigned peaked cap looked very smart but, as it came down to just above their eyes, it meant the only way that they could see the music or conductor was to tip their heads backwards. Not an ideal position to carry out any kind of work – especially whilst playing a musical instrument.

Much of the advice we offer is based on simple observation and common sense, something that we can often miss ourselves but that can be blindingly obvious to the outside observer. This is where becoming a “people watcher” can help as, by the example of others you can learn.

When it comes to our instruments we face a serious problem… tradition. Tradition can be a very important part of our lives and the basis for many aspects of important rules that we should abide by. But why is tradition so bad in relation to our instruments? Manufacturers follow tradition in order to reproduce instruments in the same way, incidentally also saving a good deal of money, and they will tell us that musicians want the instruments to stay the same whether it is the vintage Robert Carrée R-13 clarinet or the MK VI Selmer alto saxophone.

This is not exclusive to clarinets and saxophones; string instrument manufacturers also copy the great instruments of the past such as Stradivarius or Guarneri. Arguably, then, tradition is a good thing. However, when we look with new eyes on the design of a clarinet some things become clear.

The thumbrest design has remained pretty much the same for decades. It has stubbornly remained in the wrong position and a poor design despite many professional players telling manufacturers. It is not rocket science, we have opposing thumbs which means the forefinger should be inline with our thumb, watch other people pick up a pen or pencil and you will see them doing just this. It is more than likely that as clarinet players, we will (as Chris Mimnagh pointed out) have deformed ourselves through playing the clarinet so we think it is normal to have our thumb inline with our middle finger. The simple reason this is bad is because the muscles of the thumb become tense even without the weight of the instrument on it. In addition the lower position makes the right hand twist, making it difficult for players with smaller hands to cover the last hole, which is the largest!

The design of the thumbrest is also generally pretty poor, as it is a small area to support the weight, we generally move it past the knuckle joint , meaning the fingers follow and go well past their ideal position causing further tension in the right hand as we try to cover the holes.

Incorrect thumb position causing too much tension

Incorrect thumb position causing too much tension

In addition we tend to bite on the mouthpiece to try to stabilise the instrument, sub-consciously of course, this then creates potential problems with the jaw and teeth.

The simple truth is no one design of any instrument can ever truly suit all players. Perhaps we should look carefully at how we relate to our chosen instrument, the ergonomics design will have been made many years ago to suit the “normal” person, whatever that may be!

Through the ARCS workshop I recently met a lady who, in her retirement, had been hoping to improve her clarinet playing. She had put the pain in her thumb down to the arthritis she has been suffering with for years. Following discussions she came to try out for herself the latest version of the Kooiman Etude, MK 3.

She was not surprisingly a little dubious, however I was delighted to receive a message from her a week later in which she told me how wonderful it was to be able to play pain free after so many years of assuming the progressive problem with the arthritis would mean she could no longer play the clarinet.

One other sinister item we should mention is hygiene. Over the years we will probably all have seen the pretty disgusting state that some mouthpieces and reeds can get into, but do you realise how serious this might become?

In the next article there will be more advice on how to reduce the chances of discomfort or pain developing through some simple exercises and routines that should prove invaluable players of all woodwind instruments.

Following on from my International Clarinet Association presentation in Assisi, I have been invited to perform and to deliver a presentation on “Gain without Pain” at the Texas Clarinet Colloquium in Dallas at the beginning of June this year. I hope to be able to report back on this large-scale event, around 750 clarinet players will be attending! For further information on this event go to https://www.facebook.com/events/1400709943562863/?fref=ts

In an article to be published later this year, we will look at the dangers of ignoring clarinet/saxophone hygiene, ie mouthpieces reeds and pull throughs. If you have suffered from any problems that might be related to this do please get in touch either through the Editor, Richard Edwards, or email me at aroberts@theclarinet.co.uk

Andrew Roberts